- Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar 1

- Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar Release

- Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar Online

- Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar 2

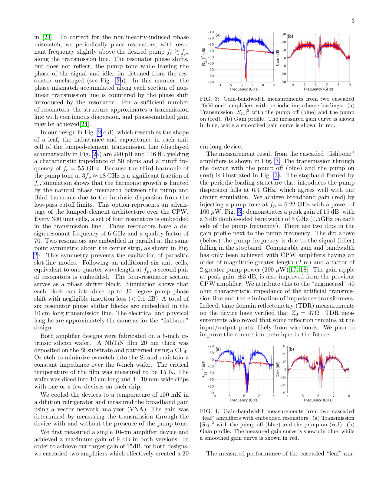

What they play are open-ended compositions, foundation motifs and figures – like the units of Unit Structures- which flourish and are referenced in determined and undetermined ways, a framework for improvisation Taylor was to use later on albums such as The Cecil Taylor Unit (New World, 1978) and 3 Phasis (New World, 1979) and in his large. '3 Phasis' is a through-composed work, more avant-classical than jazz, recorded at the last of the four sessions that also yielded 'The Cecil Taylor Unit' for New World records, NW-201. Cecil Taylor April 1978 ('3 Phasis' recording) Main Session Personnel; Raphe Malik. Trumpet: Jimmy Lyons. Alto saxophone: Cecil Taylor. Piano: Ramsey Ameen. Violin: Sirone Jones. Bass: Ronald Shannon Jackson. Drums # Tracks Playtime Issue Variance from Main Session Personnel; 1: 3 Phasis: 57:20.

Cecil Taylor died at his New York home in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, on 5 April 2018. He was 89

Born on 25 March 1929, Cecil Taylor was raised in Corona, in the New York borough of Queens. He began playing the piano at age six. He said that when he expressed an interest in the instrument, his mother informed him that he would be a doctor or a lawyer, and the piano would be his avocation. She imposed a rigorous practice schedule on him, and he became a master of the instrument, studying at the New York College of Music and the New England Conservatory. In 1955, he returned to New York and formed a quartet with soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, bassist Buell Neidlinger (who died in March), and drummer Denis Charles.

The albums Taylor made between 1956–61 featured a mix of his own compositions and pieces by Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk, as well as multiple Cole Porter tunes ('Sweet And Lovely', 'Love For Sale', and others). Even at the beginning, though, signs of music to come were obvious – his version of 'Love For Sale' begins with a solo passage that must have been breathtaking in 1959, and remains astonishing today. During two extended sessions in October 1960 and January 1961, he recorded what would ultimately become five albums' worth of material with a pool of players that included Lacy, Neidlinger, Charles, drummer Sunny Murray, trombonist Roswell Rudd, and saxophonist Archie Shepp. Shortly thereafter, he began the single most important creative relationship of his life with alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons.

Taylor, Lyons and Murray went to Europe in 1962 for a concert tour. At Copenhagen's Café Montmartre, they recorded Nefertiti, The Beautiful One Has Come, arguably the first document of Taylor's music in full flower. With Murray abandoning conventional time, and only Lyons's bebop-rooted lines to anchor them to the past, the trio took off into previously uncharted realms, combining lyricism and explosiveness for up to 20 minutes at a time. But this was to be Taylor's last recording for four years.

He signed to Blue Note in 1966, and made two albums – Unit Structures and Conquistador! – with a core group consisting of Lyons, bassists Henry Grimes and Alan Silva, and drummer Andrew Cyrille. On Unit Structures, they were joined by trumpeter Eddie Gale and reeds player Ken McIntyre; on Conquistador!, Bill Dixon played trumpet.

Taylor began to perform unaccompanied in the late 1960s, and in the 1970s made some of his most important and revelatory recordings as a solo artist, including Indent, Silent Tongues, and Air Above Mountains. From 1969–73, he taught at Antioch College in Ohio, leading a student orchestra called The Black Music Ensemble. He also taught for one year at the University of Wisconsin, where he infamously failed most of his students after they ignored his admonition to go see Miles Davis perform locally. (Taylor disliked Davis as a person, but had tremendous respect for his music.) In 1978, he was one of a group of jazz musicians invited by US President Jimmy Carter to perform at the White House.

That same year, Taylor formed arguably his greatest band – a sextet featuring trumpeter Raphé Malik, Lyons, violinist Ramsey Ameen, bassist Sirone and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. Together, they blended blues and swing with modern classical and free jazz, even nodding to African-American string bands at times – Ameen's violin was central to the group sound. But after two studio albums, The Cecil Taylor Unit and 3 Phasis, and the live albums Live In The Black Forest and One Too Many Salty Swift And Not Goodbye, they were gone, a brilliant flash that dissipated as quickly as it had appeared.

Taylor always had a fascination with dance – he famously told writer AB Spellman, 'I try to imitate on the piano the leaps in space a dancer makes.' During the late 1970s and early 1980s, he collaborated with dancer and choreographer Dianne McIntyre's group Sound In Motion, and composed and played the music for a ballet featuring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Heather Watts. His European concerts of the 1980s, featuring an ensemble that included Lyons, bassist William Parker, drummers André Martinez and Charles Downs, and Downs's wife Brenda Bakr on vocals, and also incorporated dancers at times, as in this performance filmed for German television:

In 1988, he traveled to Berlin for an extended residency documented in the massive In Berlin 88 boxset. There, he recorded duos with a variety of drummers, including Han Bennink, Louis Moholo, Tony Oxley and Günter ‘Baby' Sommer, and with guitarist Derek Bailey; led a massive ensemble of European players; conducted a workshop; and played solo. The project also inaugurated his longest running and most fruitful relationship with a label – in the 30 years since that residency, FMP has issued more than a dozen Taylor titles.

Jimmy Lyons died in 1986, and Taylor's work was fundamentally changed. He never established that kind of deep, extended partnership with another artist; indeed, other than some large ensembles, he seemed to prefer to play in trio or solo contexts, frequently switching bassists and drummers. Recordings in his final two decades were infrequent, though each one was a major statement in its own way, whether it was the 1999 summit conference Momentum Space, with saxophonist Dewey Redman and drummer Elvin Jones, the 1998 duo with violinist Mat Maneri at the Library of Congress released in 2004 as Algonquin, the 2000 performance leading the Italian Instabile Orchestra documented on 2003's The Owner Of The River Bank, or the controversial performance at the 2002 Victoriaville Festival with Bill Dixon and Tony Oxley, at which Taylor seemed to allow the trumpeter to dictate the terms, abandoning his usual torrential style in favour of gentle ripples of notes.

Taylor's piano style could be both highly percussive and volcanically melodic, but he was capable of great tenderness as well. He commanded the entire keyboard, and conventional pianos were sometimes not enough for him – whenever possible, he played a Bösendorfer Imperial, which offers nine additional keys at the lower end of the instrument's range. In her landmark book As Serious As Your Life, Valerie Wilmer famously described his style as treating the keyboard 'like 88 tuned drums', and quoted him as saying, 'We in Black music think of the piano as a percussive instrument: we beat the keyboard, we get inside the instrument.' His florid, romantic approach was entirely dependent on impeccable finger technique and astonishing speed; he mostly stayed off the pedals, preferring to punch out every note as cleanly and articulately as possible.

Taylor received numerous awards throughout his life: a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1973, a MacArthur Fellowship (the so-called ‘genius grant') in 1991, and a Kyoto Prize in 2014. In the latter case, the prize money was stolen by an acquaintance but eventually recovered. Between 1997–2016 I saw him perform five times, in various contexts from solo to leading a large ensemble, and I interviewed him in 2016 for the cover story of The Wire 386, when he was the subject of an exhibition at New York's Whitney Museum. In person, he was witty and charming, relishing the role of raconteur and happy to spend hours regaling a writer with stories about musicians he'd known in his decades-long career, periodically (and unsuccessfully) attempting to convince the museum's curator to let him smoke indoors. He was a man who decided early on in life who and what he was going to be, and never deviated from that path, no matter where it led him. In that sense, his considerable influence extends far beyond just the sound of his music; like Sun Ra or Ornette Coleman, he was an artist who insisted on his own importance and the value of his work.

In the midst of the blossoming of the free-jazz scene, pianist Cecil Taylor (1929) probably represented better than anyone else the non-jazz aspect of the movement. Many of the innovations of the 1960s were pioneered by his records. His fusion of exuberance and atonality was particularly influential.A graduate from the New England Conservatory of Music (1951-1955), where he had studied contemporary classical music, Taylor developed a radical improvising style at the piano that indulged in tone clusters, percussive attacks and irregular polyrhythmic patterns, a very 'physical' style that required a manic energy during lengthy and frenzied performances, a somewhat 'cacophonous' style that relished both atonal and tonal passages. The dynamic range of his improvisations was virtually infinite.

His maturation took place via Charge 'Em Blues, off Jazz Advance (december 1955), for his first quartet, featuring soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, bassist Buell Neidlinger and drummer Dennis Charles, the convoluted, tonally ambiguous Tune 2 off At Newport (july 1956) for the same quartet, Toll (the blueprint for many of his classics), Of What and Excursion on a Wobbly Rail, off Looking Ahead (june 1958), with Lacy replaced by vibraphonist Earl Griffith, Little Lees and Matie's Trophies, off Love for Sale (april 1959), with trumpeter Ted Curson, saxophonist Bill Barron and the usual rhythm section, Air and E.B., off The World of Cecil Taylor (october 1960), featuring Archie Shepp on tenor saxophone and the same rhythm section, the abstract Cell Walk For Celeste, off New York City R&B (january 1961), also for the quartet of Taylor, Shepp, Charles and Neidlinger (to whom the album was credited), Mixed, off Gil Evans' Into The Hot (october 1961), featuring the brand new line-up of altoist Jimmy Lyons, tenorist Archie Shepp, bassist Henry Grimes, drummer Sunny Murray, trumpeter Ted Curson and trombonist Roswell Rudd. These albums were still anchored to the song format and wasted time on other people's material when Taylor's own compositions were so much superior; but occasionally the pianist and his cohorts launched into strident, torrential jamming that obliterated the history of jazz. Taylor's group was much bolder in their live performances, when they indulged in lengthy improvisations in front of an audience that still thought of jazz as light entertainment. Taylor's compositions at their best were wildly irregular and casually nonchalant at the same time. They were bold contradictions. Sometimes dramatic and sometimes sarcastic, they straddled the line between being and not being. At the same time, pieces such as Tune 2, Toll, Air, Cell Walk For Celeste and Mixed displayed the formalist concern typical of classical music.

Taylor and Coltrane recorded together only the sessions of Stereo Drive (october 1958), also known as Hard Driving Jazz and Coltrane Time, in a quintet with trumpeter Kenny Dorham.

Taylor's first major statement came with the live trio performances of Nefertiti the Beautiful One Has Come (november 1962), featuring Jimmy Lyons on alto and Sunny Murray on drums (the Unit), two ideal complements for Taylor's explosive style. These lengthy and complex jams, Trance, Lena, Nefertiti The Beautiful One Has Come and the 21-minute colossus D Trad That's What, were as uncompromising as Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz (1960) and John Coltrane's Impressions (1961). In fact, they were so uncompromising that very few people listened to them. Basically, the ambiguity that was one of the two sides of Taylor's early music acquired a life of its own, progressively cannibalizing the other side. In parallel the piano's role kept expanding, at times sounding like Taylor wanted to play the entire orchestra on just one hyper-active instrument (and maybe simultaneously).

Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar 1

It took three years for Taylor to release another album, and it presented a larger ensemble and an even wilder sound, as violent as garage-rock, bordering on hysteria: Unit Structures (may 1966) featured (mostly) a septet with Lyons, Eddie Gale Stevens on trumpet, Ken McIntyre on alto sax, oboe and bass clarinet, two bassists (Henry Grimes and Alan Silva) and Andrew Cyrille on drums. These pieces (or, better, 'structures') were conceived as sequences of polyphonic events rather than, say, series of variations on a theme. Nonetheless, Unit Structure, Enter Evening and Steps were highly structured compositions, and therein lied Taylor's uniqueness: his 'free jazz' was also 'free' of the melodrama that permeated Coltrane's and Coleman's music. Despite all the furor, Taylor's music always sounded firmly under the control of a cold intelligence. Cyrille's drumming was less abstract than Murray, more integrated with the other players, but Silva now played the 'decorative' role that Murray used to play. The sextet of Conquistador (october 1966), featuring Bill Dixon on trumpet, Lyons, and the same three-piece rhythm section, pushed the experiment to its limits in two shockingly abrasive and expressionistic side-long jams, Conquistador and With. Their sheer size challenged the balance between disintegration and integration, looseness and cohesiveness, that constituted the soul of the previous 'structures'. The flow of enigmatic sounds had become a puzzle to be reconstructed. A quartet of Taylor, Lyons, Silva and Cyrille recorded Student Studies: (november 1966), containing the 27-minute Student Studies, the 20-minute Amplitude and the 12-minute Niggle Feuigle, that stepped back a bit from the edge, emphasizing the structure behind the chaos, the 'jazz' soul hidden under the apparently dissolute dissonance.

However, Taylor's music was still underappreciated and he had to spend the next seven years virtually in exile. During this period Taylor composed/improvised some of his most daring music: the four-movement Praxis (july 1968) for solo piano, released in 1982, the six-movement Second Act Of A (july 1969), for a quartet with Lyons, Cyrille and soprano saxophonist Sam Rivers, the three-movement Indent (march 1973) for solo piano, released on Mysteries, the 81-minute Bulu Akisakila Kutala (may 1973) for a trio with Lyons and Cyrille, released on Akisakila (1973),

Solo (May 1973), his first collection of solo-piano pieces, presented Taylor's 'layering' technique in its most sophisticated version. The organized improvisations of Choral of Voice, Lono, Asapk in Ame and especially Indent were emblematic of the process of cooperation and competition of events operating at different levels. Spring of Two Blue J's (november 1973) contained two versions of the piece, one solo and one for a quartet with Lyons, Cyrille and bassist Sirone. The solo version delivered his most emotional outpour yet.

This period culminated in the five loud and noisy movements of the live solo-piano suite Silent Tongues (july 1974): Abyss, Petals & Filaments (combined into one 18-minute track), Jitney (18 minutes), Crossing (18 minutes divided into two tracks) and After all (ten minutes). This album was a compendium of Taylor's aesthetic, secreting an unlikely synthesis of the irrational and the rational that had been the contradicting pillars of his music. Its range of moods defied the laws of psychoanalysis. The sound was emblematic of his brilliant exuberance but was soon surpassed in intensity by at least two (clearly much more improvised) performances: the 62-minute Streams and Chorus of Seed (june 1976), released on Dark To Themselves, for a quintet with Lyons, trumpeter Raphe Malik, drummer Marc Edwards and tenor saxophonist David Ware, and the 76-minute solo-piano Air Above Mountains (august 1976). Here the music was meant to exhaust the performer, to last until it had drained every gram of psychological and physical energy out of the performer. But these live juggernauts also marked the end of the 'underground' period and the beginning of a three-year artistic bonanza.

A sextet of Taylor, Lyons, trumpeter Raphe Malik, violinist Ramsey Ameen, bassist Norris 'Sirone' Jones and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson delivered the more structured and variegated jams of Cecil Taylor Unit (april 1978): the 14-minute Idut, the 14-minute Serdab, the 30-minute Holiday En Masque, and the 57-minute 3 Phasis (april 1978). A similar sextet with Lyons, Ameen, Alan Silva on bass and cello and both Jerome Cooper and Sunny Murray on drums, recorded the 69-minute Is it the Brewing Luminous (february 1980). Despite the monumental proportions, this music was less magniloquent and less mysterious than the music of the 1960s.

Live In The Black Forest (june 1978) contains two lengthy compositions, The Eel Pot and Sperichill On Calling, performed by a sextet including Jimmy Lyons (alto sax), Raphe Malik (trumpet), Ramsey Ameen (violin), Sirone (bass) and Ronald Shannon Jackson (drums).

Starting with the quartet effort Calling it the 8th (november 1981), featuring Lyons, bassist William Parker and drummer Rashid Bakr (all of them doubling on voice), and the solos Fly Fly Fly Fly Fly (september 1980), containing the ten-minute Rocks Sub Amba and the nine-minute The Stele Stolen And Broken Is Reclaimed, and Garden (november 1981) and Garden 2nd Set (november 1981), Taylor increased the production values to emphasize the nuances of his playing, adopted a jazzier style and added his poetry to the music (not a welcomed addition).

A new prolific phase of his career yielded recordings for ensemble, such as Winged Serpent (october 1984) and the 48-minute Legba Crossing (july 1988); for solo piano, such as For Olim (april 1986), containing the 18-minute title-track, the 71-minute title-track of Erzulie Maketh Scent (july 1988) and and the 72-minute The Tree of Life (march 1991), perhaps the most austere of his life; and for small groups, such as Olu Iwa (april 1986), containing the 48-minute B Ee Ba Nganga Ban'a Eee for piano, trombone, tenor sax and rhythm section, and the 27-minute Olu Iwa for piano and rhythm section, the precursor of his many piano and drums duets, as well as the 61-minute The Hearth (june 1988), for a trio with saxophonist Evan Parker and cellist Tristan Honsinger, and Looking (november 1989) and Celebrated Blazons (june 1990) for the trio with bassist William Parker and drummer Tony Oxley.

Duets 1992 documents a studio collaboration between Cecil Taylor and Bill Dixon.

The best fusion of his visceral and romantic sides was perhaps achieved on Always A Pleasure (april 1993), a live workshop (Longineu Parsons on trumpet, Harri Sjoestroem on soprano sax, Charles Gayle on tenor sax, Tristan Honsinger on cello, Sirone on bass, Rashid Bakr on drums).

All The Notes (february 2000) contains three improvisations with Dominic Duval on bass and Jackson Krall on drums.

Other live albums included: the ten-disc box-set 2 Ts For A Lovely T (september 1990), featuring bassist William Parker and drummer Tony Oxley; Willisau Concert (september 2000), a solo performance; Almeda (november 1996), with Tristan Honsinger on cello, Dominic Duval on double bass, Jackson Krall on drums, Chris Matthay on trumpet, Jeff Hoyer on trombone, Chris Jonas on alto, Harri Sjöström on soprano and Elliot Levin on tenor; CT: The Dance Project (july 1990) in a trio with bassist William Parker and percussionist Masashi Harada; the trio of Cecil Taylor/ Bill Dixon/ Tony Oxley (may 2002); Ailanthus/Altissima (Bilateral Dimensions Of 2 Root Songs) (recorded in 2008) with drummer Tony Oxley.

- Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar 1

- Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar Release

- Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar Online

- Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar 2

What they play are open-ended compositions, foundation motifs and figures – like the units of Unit Structures- which flourish and are referenced in determined and undetermined ways, a framework for improvisation Taylor was to use later on albums such as The Cecil Taylor Unit (New World, 1978) and 3 Phasis (New World, 1979) and in his large. '3 Phasis' is a through-composed work, more avant-classical than jazz, recorded at the last of the four sessions that also yielded 'The Cecil Taylor Unit' for New World records, NW-201. Cecil Taylor April 1978 ('3 Phasis' recording) Main Session Personnel; Raphe Malik. Trumpet: Jimmy Lyons. Alto saxophone: Cecil Taylor. Piano: Ramsey Ameen. Violin: Sirone Jones. Bass: Ronald Shannon Jackson. Drums # Tracks Playtime Issue Variance from Main Session Personnel; 1: 3 Phasis: 57:20.

Cecil Taylor died at his New York home in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, on 5 April 2018. He was 89

Born on 25 March 1929, Cecil Taylor was raised in Corona, in the New York borough of Queens. He began playing the piano at age six. He said that when he expressed an interest in the instrument, his mother informed him that he would be a doctor or a lawyer, and the piano would be his avocation. She imposed a rigorous practice schedule on him, and he became a master of the instrument, studying at the New York College of Music and the New England Conservatory. In 1955, he returned to New York and formed a quartet with soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, bassist Buell Neidlinger (who died in March), and drummer Denis Charles.

The albums Taylor made between 1956–61 featured a mix of his own compositions and pieces by Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk, as well as multiple Cole Porter tunes ('Sweet And Lovely', 'Love For Sale', and others). Even at the beginning, though, signs of music to come were obvious – his version of 'Love For Sale' begins with a solo passage that must have been breathtaking in 1959, and remains astonishing today. During two extended sessions in October 1960 and January 1961, he recorded what would ultimately become five albums' worth of material with a pool of players that included Lacy, Neidlinger, Charles, drummer Sunny Murray, trombonist Roswell Rudd, and saxophonist Archie Shepp. Shortly thereafter, he began the single most important creative relationship of his life with alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons.

Taylor, Lyons and Murray went to Europe in 1962 for a concert tour. At Copenhagen's Café Montmartre, they recorded Nefertiti, The Beautiful One Has Come, arguably the first document of Taylor's music in full flower. With Murray abandoning conventional time, and only Lyons's bebop-rooted lines to anchor them to the past, the trio took off into previously uncharted realms, combining lyricism and explosiveness for up to 20 minutes at a time. But this was to be Taylor's last recording for four years.

He signed to Blue Note in 1966, and made two albums – Unit Structures and Conquistador! – with a core group consisting of Lyons, bassists Henry Grimes and Alan Silva, and drummer Andrew Cyrille. On Unit Structures, they were joined by trumpeter Eddie Gale and reeds player Ken McIntyre; on Conquistador!, Bill Dixon played trumpet.

Taylor began to perform unaccompanied in the late 1960s, and in the 1970s made some of his most important and revelatory recordings as a solo artist, including Indent, Silent Tongues, and Air Above Mountains. From 1969–73, he taught at Antioch College in Ohio, leading a student orchestra called The Black Music Ensemble. He also taught for one year at the University of Wisconsin, where he infamously failed most of his students after they ignored his admonition to go see Miles Davis perform locally. (Taylor disliked Davis as a person, but had tremendous respect for his music.) In 1978, he was one of a group of jazz musicians invited by US President Jimmy Carter to perform at the White House.

That same year, Taylor formed arguably his greatest band – a sextet featuring trumpeter Raphé Malik, Lyons, violinist Ramsey Ameen, bassist Sirone and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. Together, they blended blues and swing with modern classical and free jazz, even nodding to African-American string bands at times – Ameen's violin was central to the group sound. But after two studio albums, The Cecil Taylor Unit and 3 Phasis, and the live albums Live In The Black Forest and One Too Many Salty Swift And Not Goodbye, they were gone, a brilliant flash that dissipated as quickly as it had appeared.

Taylor always had a fascination with dance – he famously told writer AB Spellman, 'I try to imitate on the piano the leaps in space a dancer makes.' During the late 1970s and early 1980s, he collaborated with dancer and choreographer Dianne McIntyre's group Sound In Motion, and composed and played the music for a ballet featuring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Heather Watts. His European concerts of the 1980s, featuring an ensemble that included Lyons, bassist William Parker, drummers André Martinez and Charles Downs, and Downs's wife Brenda Bakr on vocals, and also incorporated dancers at times, as in this performance filmed for German television:

In 1988, he traveled to Berlin for an extended residency documented in the massive In Berlin 88 boxset. There, he recorded duos with a variety of drummers, including Han Bennink, Louis Moholo, Tony Oxley and Günter ‘Baby' Sommer, and with guitarist Derek Bailey; led a massive ensemble of European players; conducted a workshop; and played solo. The project also inaugurated his longest running and most fruitful relationship with a label – in the 30 years since that residency, FMP has issued more than a dozen Taylor titles.

Jimmy Lyons died in 1986, and Taylor's work was fundamentally changed. He never established that kind of deep, extended partnership with another artist; indeed, other than some large ensembles, he seemed to prefer to play in trio or solo contexts, frequently switching bassists and drummers. Recordings in his final two decades were infrequent, though each one was a major statement in its own way, whether it was the 1999 summit conference Momentum Space, with saxophonist Dewey Redman and drummer Elvin Jones, the 1998 duo with violinist Mat Maneri at the Library of Congress released in 2004 as Algonquin, the 2000 performance leading the Italian Instabile Orchestra documented on 2003's The Owner Of The River Bank, or the controversial performance at the 2002 Victoriaville Festival with Bill Dixon and Tony Oxley, at which Taylor seemed to allow the trumpeter to dictate the terms, abandoning his usual torrential style in favour of gentle ripples of notes.

Taylor's piano style could be both highly percussive and volcanically melodic, but he was capable of great tenderness as well. He commanded the entire keyboard, and conventional pianos were sometimes not enough for him – whenever possible, he played a Bösendorfer Imperial, which offers nine additional keys at the lower end of the instrument's range. In her landmark book As Serious As Your Life, Valerie Wilmer famously described his style as treating the keyboard 'like 88 tuned drums', and quoted him as saying, 'We in Black music think of the piano as a percussive instrument: we beat the keyboard, we get inside the instrument.' His florid, romantic approach was entirely dependent on impeccable finger technique and astonishing speed; he mostly stayed off the pedals, preferring to punch out every note as cleanly and articulately as possible.

Taylor received numerous awards throughout his life: a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1973, a MacArthur Fellowship (the so-called ‘genius grant') in 1991, and a Kyoto Prize in 2014. In the latter case, the prize money was stolen by an acquaintance but eventually recovered. Between 1997–2016 I saw him perform five times, in various contexts from solo to leading a large ensemble, and I interviewed him in 2016 for the cover story of The Wire 386, when he was the subject of an exhibition at New York's Whitney Museum. In person, he was witty and charming, relishing the role of raconteur and happy to spend hours regaling a writer with stories about musicians he'd known in his decades-long career, periodically (and unsuccessfully) attempting to convince the museum's curator to let him smoke indoors. He was a man who decided early on in life who and what he was going to be, and never deviated from that path, no matter where it led him. In that sense, his considerable influence extends far beyond just the sound of his music; like Sun Ra or Ornette Coleman, he was an artist who insisted on his own importance and the value of his work.

In the midst of the blossoming of the free-jazz scene, pianist Cecil Taylor (1929) probably represented better than anyone else the non-jazz aspect of the movement. Many of the innovations of the 1960s were pioneered by his records. His fusion of exuberance and atonality was particularly influential.A graduate from the New England Conservatory of Music (1951-1955), where he had studied contemporary classical music, Taylor developed a radical improvising style at the piano that indulged in tone clusters, percussive attacks and irregular polyrhythmic patterns, a very 'physical' style that required a manic energy during lengthy and frenzied performances, a somewhat 'cacophonous' style that relished both atonal and tonal passages. The dynamic range of his improvisations was virtually infinite.

His maturation took place via Charge 'Em Blues, off Jazz Advance (december 1955), for his first quartet, featuring soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, bassist Buell Neidlinger and drummer Dennis Charles, the convoluted, tonally ambiguous Tune 2 off At Newport (july 1956) for the same quartet, Toll (the blueprint for many of his classics), Of What and Excursion on a Wobbly Rail, off Looking Ahead (june 1958), with Lacy replaced by vibraphonist Earl Griffith, Little Lees and Matie's Trophies, off Love for Sale (april 1959), with trumpeter Ted Curson, saxophonist Bill Barron and the usual rhythm section, Air and E.B., off The World of Cecil Taylor (october 1960), featuring Archie Shepp on tenor saxophone and the same rhythm section, the abstract Cell Walk For Celeste, off New York City R&B (january 1961), also for the quartet of Taylor, Shepp, Charles and Neidlinger (to whom the album was credited), Mixed, off Gil Evans' Into The Hot (october 1961), featuring the brand new line-up of altoist Jimmy Lyons, tenorist Archie Shepp, bassist Henry Grimes, drummer Sunny Murray, trumpeter Ted Curson and trombonist Roswell Rudd. These albums were still anchored to the song format and wasted time on other people's material when Taylor's own compositions were so much superior; but occasionally the pianist and his cohorts launched into strident, torrential jamming that obliterated the history of jazz. Taylor's group was much bolder in their live performances, when they indulged in lengthy improvisations in front of an audience that still thought of jazz as light entertainment. Taylor's compositions at their best were wildly irregular and casually nonchalant at the same time. They were bold contradictions. Sometimes dramatic and sometimes sarcastic, they straddled the line between being and not being. At the same time, pieces such as Tune 2, Toll, Air, Cell Walk For Celeste and Mixed displayed the formalist concern typical of classical music.

Taylor and Coltrane recorded together only the sessions of Stereo Drive (october 1958), also known as Hard Driving Jazz and Coltrane Time, in a quintet with trumpeter Kenny Dorham.

Taylor's first major statement came with the live trio performances of Nefertiti the Beautiful One Has Come (november 1962), featuring Jimmy Lyons on alto and Sunny Murray on drums (the Unit), two ideal complements for Taylor's explosive style. These lengthy and complex jams, Trance, Lena, Nefertiti The Beautiful One Has Come and the 21-minute colossus D Trad That's What, were as uncompromising as Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz (1960) and John Coltrane's Impressions (1961). In fact, they were so uncompromising that very few people listened to them. Basically, the ambiguity that was one of the two sides of Taylor's early music acquired a life of its own, progressively cannibalizing the other side. In parallel the piano's role kept expanding, at times sounding like Taylor wanted to play the entire orchestra on just one hyper-active instrument (and maybe simultaneously).

Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar 1

It took three years for Taylor to release another album, and it presented a larger ensemble and an even wilder sound, as violent as garage-rock, bordering on hysteria: Unit Structures (may 1966) featured (mostly) a septet with Lyons, Eddie Gale Stevens on trumpet, Ken McIntyre on alto sax, oboe and bass clarinet, two bassists (Henry Grimes and Alan Silva) and Andrew Cyrille on drums. These pieces (or, better, 'structures') were conceived as sequences of polyphonic events rather than, say, series of variations on a theme. Nonetheless, Unit Structure, Enter Evening and Steps were highly structured compositions, and therein lied Taylor's uniqueness: his 'free jazz' was also 'free' of the melodrama that permeated Coltrane's and Coleman's music. Despite all the furor, Taylor's music always sounded firmly under the control of a cold intelligence. Cyrille's drumming was less abstract than Murray, more integrated with the other players, but Silva now played the 'decorative' role that Murray used to play. The sextet of Conquistador (october 1966), featuring Bill Dixon on trumpet, Lyons, and the same three-piece rhythm section, pushed the experiment to its limits in two shockingly abrasive and expressionistic side-long jams, Conquistador and With. Their sheer size challenged the balance between disintegration and integration, looseness and cohesiveness, that constituted the soul of the previous 'structures'. The flow of enigmatic sounds had become a puzzle to be reconstructed. A quartet of Taylor, Lyons, Silva and Cyrille recorded Student Studies: (november 1966), containing the 27-minute Student Studies, the 20-minute Amplitude and the 12-minute Niggle Feuigle, that stepped back a bit from the edge, emphasizing the structure behind the chaos, the 'jazz' soul hidden under the apparently dissolute dissonance.

However, Taylor's music was still underappreciated and he had to spend the next seven years virtually in exile. During this period Taylor composed/improvised some of his most daring music: the four-movement Praxis (july 1968) for solo piano, released in 1982, the six-movement Second Act Of A (july 1969), for a quartet with Lyons, Cyrille and soprano saxophonist Sam Rivers, the three-movement Indent (march 1973) for solo piano, released on Mysteries, the 81-minute Bulu Akisakila Kutala (may 1973) for a trio with Lyons and Cyrille, released on Akisakila (1973),

Solo (May 1973), his first collection of solo-piano pieces, presented Taylor's 'layering' technique in its most sophisticated version. The organized improvisations of Choral of Voice, Lono, Asapk in Ame and especially Indent were emblematic of the process of cooperation and competition of events operating at different levels. Spring of Two Blue J's (november 1973) contained two versions of the piece, one solo and one for a quartet with Lyons, Cyrille and bassist Sirone. The solo version delivered his most emotional outpour yet.

This period culminated in the five loud and noisy movements of the live solo-piano suite Silent Tongues (july 1974): Abyss, Petals & Filaments (combined into one 18-minute track), Jitney (18 minutes), Crossing (18 minutes divided into two tracks) and After all (ten minutes). This album was a compendium of Taylor's aesthetic, secreting an unlikely synthesis of the irrational and the rational that had been the contradicting pillars of his music. Its range of moods defied the laws of psychoanalysis. The sound was emblematic of his brilliant exuberance but was soon surpassed in intensity by at least two (clearly much more improvised) performances: the 62-minute Streams and Chorus of Seed (june 1976), released on Dark To Themselves, for a quintet with Lyons, trumpeter Raphe Malik, drummer Marc Edwards and tenor saxophonist David Ware, and the 76-minute solo-piano Air Above Mountains (august 1976). Here the music was meant to exhaust the performer, to last until it had drained every gram of psychological and physical energy out of the performer. But these live juggernauts also marked the end of the 'underground' period and the beginning of a three-year artistic bonanza.

A sextet of Taylor, Lyons, trumpeter Raphe Malik, violinist Ramsey Ameen, bassist Norris 'Sirone' Jones and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson delivered the more structured and variegated jams of Cecil Taylor Unit (april 1978): the 14-minute Idut, the 14-minute Serdab, the 30-minute Holiday En Masque, and the 57-minute 3 Phasis (april 1978). A similar sextet with Lyons, Ameen, Alan Silva on bass and cello and both Jerome Cooper and Sunny Murray on drums, recorded the 69-minute Is it the Brewing Luminous (february 1980). Despite the monumental proportions, this music was less magniloquent and less mysterious than the music of the 1960s.

Live In The Black Forest (june 1978) contains two lengthy compositions, The Eel Pot and Sperichill On Calling, performed by a sextet including Jimmy Lyons (alto sax), Raphe Malik (trumpet), Ramsey Ameen (violin), Sirone (bass) and Ronald Shannon Jackson (drums).

Starting with the quartet effort Calling it the 8th (november 1981), featuring Lyons, bassist William Parker and drummer Rashid Bakr (all of them doubling on voice), and the solos Fly Fly Fly Fly Fly (september 1980), containing the ten-minute Rocks Sub Amba and the nine-minute The Stele Stolen And Broken Is Reclaimed, and Garden (november 1981) and Garden 2nd Set (november 1981), Taylor increased the production values to emphasize the nuances of his playing, adopted a jazzier style and added his poetry to the music (not a welcomed addition).

A new prolific phase of his career yielded recordings for ensemble, such as Winged Serpent (october 1984) and the 48-minute Legba Crossing (july 1988); for solo piano, such as For Olim (april 1986), containing the 18-minute title-track, the 71-minute title-track of Erzulie Maketh Scent (july 1988) and and the 72-minute The Tree of Life (march 1991), perhaps the most austere of his life; and for small groups, such as Olu Iwa (april 1986), containing the 48-minute B Ee Ba Nganga Ban'a Eee for piano, trombone, tenor sax and rhythm section, and the 27-minute Olu Iwa for piano and rhythm section, the precursor of his many piano and drums duets, as well as the 61-minute The Hearth (june 1988), for a trio with saxophonist Evan Parker and cellist Tristan Honsinger, and Looking (november 1989) and Celebrated Blazons (june 1990) for the trio with bassist William Parker and drummer Tony Oxley.

Duets 1992 documents a studio collaboration between Cecil Taylor and Bill Dixon.

The best fusion of his visceral and romantic sides was perhaps achieved on Always A Pleasure (april 1993), a live workshop (Longineu Parsons on trumpet, Harri Sjoestroem on soprano sax, Charles Gayle on tenor sax, Tristan Honsinger on cello, Sirone on bass, Rashid Bakr on drums).

All The Notes (february 2000) contains three improvisations with Dominic Duval on bass and Jackson Krall on drums.

Other live albums included: the ten-disc box-set 2 Ts For A Lovely T (september 1990), featuring bassist William Parker and drummer Tony Oxley; Willisau Concert (september 2000), a solo performance; Almeda (november 1996), with Tristan Honsinger on cello, Dominic Duval on double bass, Jackson Krall on drums, Chris Matthay on trumpet, Jeff Hoyer on trombone, Chris Jonas on alto, Harri Sjöström on soprano and Elliot Levin on tenor; CT: The Dance Project (july 1990) in a trio with bassist William Parker and percussionist Masashi Harada; the trio of Cecil Taylor/ Bill Dixon/ Tony Oxley (may 2002); Ailanthus/Altissima (Bilateral Dimensions Of 2 Root Songs) (recorded in 2008) with drummer Tony Oxley.

Poschiavo (may 1999) contains a solo piano performance.

The Last Dance Vol. 1 & 2 (spring 2003) was a collaboration with bassist Dominic Duval.

Cecil Taylor and Pauline Oliveros collaborated on the live Solo Duo Poetry (october 2008) - Independent, 2012).

Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar Release

A quintet with Jimmy Lyons (alto sax), David Ware (tenor sax), Raphe Malik (trumpet) and Marc Edwards (drums), recorded the live Michigan State University April 15th 1976 (april 1976), including the 14-minute Petals and the 32-minute three-movement suite Wavelets.

Duets with Tony Oxley are documented on Conversation With Tony Oxley (february 2008) and Birdland/Neuburg 2011 (november 2011).

Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar Online

Taylor represented everything that Coleman stood against: he had studied composition (Coleman was illiterate) and he was inspired by atonal music (Coleman harked back to older black music). Coleman approached dance music from the viewpoint of the disco. Taylor's music was frequently compared (by himself) to classical ballet. Even the mood was opposite: Taylor's music was an atomic bomb compared to Coleman's passion.

Cecil Taylor 3 Phases Rar 2

Cecil Taylor died in 2018 at the age of 89.